For information about how you can support your Neurodivergent colleagues and create a positive workplace culture, see our sister guidance Support for those working with and/or managing neurodivergent SLTs

For terminology, refer to our Neurodivergence Glossary

View References for the guidance

Back to Guidance for and to support neurodivergent SLTs in their careers

Last updated: October 2024

About this guidance

This guidance uses identity-first language throughout (e.g., autistic instead of person with autism). This decision has been made in line with the current dominant preference of neurodivergent individuals within the wider literature (e.g. Walker, 2021; Keating et al, 2023). Where this guidance refers to SLTs it also refers to SLTAs, SLT students and SLT apprentices unless the context relates to qualified SLTs only.

Neurodivergent is a broad term, which encompasses (but is not limited to) some of the below diagnoses (Learn more about neurodivergence types; Doyle, 2020).

- Autism

- ADHD

- Specific learning impairments (e.g., dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, or dysgraphia)

- Tourette Syndrome

- Intellectual (or learning) disability

- Down Syndrome

- Williams Syndrome

- Sensory Processing Disorder

- Developmental Language Disorder

- Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)

- Mental health conditions (e.g. bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, PTSD)

- Acquired neurodivergence (including conditions resulting from stroke and brain injury)

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Symptomatic hypermobility (e.g. Ehler Danlos Syndrome, Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder)

A full list of terminology used throughout this guidance can be found in the Neurodivergence glossary.

We appreciate and acknowledge that the recommendations set out in this guidance may not be accessible or appropriate for all workplaces or settings. We ask that adjustments are considered on an individual basis and we hope this promotes open conversations and discussions on how we can make the workforce more accessible and inclusive.

This guidance does not provide legal advice, but links to relevant pieces of legislation are included for completeness. What is reasonable depends on each situation and considerations might take into account health and safety, whether it reduces disadvantage, affordability and practicality. See gov.uk for the definition of what is ‘reasonable’.

These guidelines are co-produced by members of UK Neurodivergent Speech & Language Therapy Professionals Peer Support Group (NDSLTUK) and members of the RCSLT Disability Working Group, which included speech and language therapists (SLTs), speech and language therapy assistants (SLTAs), newly qualified practitioners (NQPs) and SLT students, representing a diverse range of neurodivergent neurominorities, including ADHD, Autism, Dyslexic, Dyspraxic (DCD), acquired brain injury (ABI), mental health conditions, with support and guidance from RCSLT.

RCSLT’s strategic vision contains specific commitments to promoting greater equality, diversity and inclusion. It aspires to a more diverse student population and workforce, including those with a disability. This guidance explores how those commitments can be embraced by the whole profession to support neurodivergent SLTs.

Please note:

This resource does not contain clinical guidance for SLTs on working with service users who are neurodivergent. This resource does not cover SLT pre-registration students whilst at university, though it can be applied to their experiences whilst on placement.

For relevant information on these topics, please see our guidance on:

Introduction

Neurodivergent SLTs may have a variety of both individual strengths and areas of need, which can impact on their ability to function at their best within the workplace. These sections look at the different aspects of working life and how neurodivergent SLTs can best be supported at every stage.

There is a varied and wide scope of neurodivergent minority types and the differences in the way these may present within and between individuals at different times and within different environments. Individual experiences will also be directly impacted upon by coexisting protected characteristics, life experiences, and individual differences. Consequently, the support that a neurodivergent individual requires must be dynamic, intersectional, and person-specific.

An important first step in accessing appropriate support is to complete a reflection or supported assessment on individual strengths and areas of need. This is something which may be completed personally, within a supervised session, or by accessing an internal or external service (e.g., occupational health services, or the Access to Work scheme). Managers may need to develop their own skills or seek further specialist training or coaching to support with this. Professionals should not solely rely on or apply clinical knowledge to their colleagues, because this knowledge may be outdated or not applicable to work-based activity. See guidance for those working with and/or managing ND employees.

The support required by an individual may relate to or include (but is not limited to):

- environmental modifications

- flexible working patterns

- completion of specific duties

- technological adaptations (including the use of Alternative and Augmentative Communication (AAC))

- access to additional mentorship, neurodiversity coaching, counselling, supervision, or other specialist support

- time off to attend or access appointments. Some employers have disability policies that may outline the details of whether this is paid time off.

- adjustments to overall workload, including modification of job plans, also known as ‘job carving’, to reflect individual strengths and areas of need

- adjustments to the recruitment process / career progression.

However, we acknowledge that many neurodivergent individuals may find it challenging to know and understand their own needs, or what adjustments they require or are able to access. This may be due to challenges around interoception, the impact of late diagnosis, or experiences of previous discrimination. As such, access to external or internal support agencies may be beneficial in understanding and assessing these needs on a practical level.

Neurodivergent individuals are also at increased risk of experiencing co-occurring physical and mental health needs, some of which may be directly related to the experience of navigating a neurotypical world. Longstanding interoceptive and communication differences and a history of not being believed may mean some have been unable to recognise or label chronic pain, such as conditions related to symptomatic hypermobility or autoimmunology, and often misdiagnosed with anxiety, chronic illness or no diagnosis at all. As such, it is important to consider how these other conditions may impact upon day-to-day functioning including accessing appropriate support to avoid burnout.

Burnout within neurodivergent individuals may look vastly different to burnout within the neurotypical population. It may be characterised by a short-term or long-term loss of skills and ability to function, along with mild to severe mental and physical health symptoms (including increased anxiety, low mood, and somatosensory symptoms). This can require the individual to take prolonged time off work to address and recover from the burnout.

Neurodivergent individuals may also mask their difficulties, sometimes unconsciously (Pearson & Rose, 2023). Masking is when a person artificially performs behaviours which are presumed to be more socially acceptable (Hull et al, 2019). It may involve the suppression of neurodivergent behaviours or characteristics, including self-stimulatory or self-regulating behaviours. This can lead to feelings of overwhelm, guilt over not being able to cope, and lead to others being surprised when they learn of the level of difficulty the individual is experiencing (Cook et al, 2021).

This guidance seeks to provide practical guidance for neurodivergent individuals, and their colleagues and employers, to support a more inclusive workplace and profession.

Resources for those who wish to explore their neurodivergence:

I think I might have ADHD

- Adult ADHD Screen Survey ADHD UK

- Often unknown challenges of ADHD: ADHD Factsheet

- The Black Women Breaking the Stigma Around ADHD

- Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of ADHD in girls and women

- 100 Q&As about ADHD in women and girls

- HOW TO ADHD Website / YouTube channel

- 5 minute video about the importance of identifying and treating ADHD

I think I might be Autistic

- The ultimate autism resource Embrace Autism

- What is Autism? AutisticSLT

- Autism and Late Diagnosis Q&A with two autistic adults

- Cambridge’s youngest Black professor, Jason Arday on Autism, racism, and learning to read at 18

I think I might have Dyscalculia, Dyspraxia or Dyslexia

- Dyspraxia Test

- Dyspraxia checklist

- Dyspraxia Initial Screening Checklist

- Dyslexia Screen for Adults

- Dyslexia checklist for adults

- Dyscalculia Screen for adults

Documenting Neurodivergent strengths and needs

Health Adjustment Passport template, NHS Employers

Applying for jobs

Reasonable Adjustments for Interviews

Accessibility should be considered at all stages of the recruitment process. Employers must consider reasonable adjustments as outlined in the Equality Act (2010) during the recruitment process. Employers who have signed up to the ‘Disability Confident’ scheme commit to offer disabled people an interview if they meet the minimum criteria for the job vacancy, subject to some exceptions.

Employers should ask all candidates whether they require adjustments, regardless of whether they have a disclosed disability or not. Making simple changes that are applied to all candidates is a good way to ensure interviews are fully inclusive. Some neurodivergent people will not consider themselves as disabled, or may not feel comfortable disclosing their diagnosis for fear of unconscious bias and discrimination, however, they may still benefit from interview adjustments. Reasonable adjustments should be discussed on an individual basis.

“Across my teams, all interview questions are sent out to all candidates the day before the interview. This process is described in the job adverts. The reason for sharing the information beforehand, is to avoid people having to ask for questions, which unintentionally could create an unconscious bias. I have found answers to questions are more reflective and thoughtful and as such the change to process has been positive. On occasion, people will be given an unseen task, on those occasions, we describe the nature of the task beforehand but otherwise all other questions are seen prior to interview.”

Heidi, Head of Service

Asking for adjustments

- Consider when and how to disclose, if at all.

- Request adjustments as early as possible.

- Summarise needs in written form such as email, so there is a written record. This can subsequently be used as evidence if the employer refuses the adjustments required.

- Do not assume that the hiring manager or interview panel members know about your disclosed disability.

Individuals can seek advice from Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration service (ACAS) for advice or Citzen’s Advice for free legal help if they are being discriminated against. Refusing to implement requested adjustments because it seems ‘unfair’ to others is an example of direct discrimination. See this article about an autistic man who won compensation after being refused the reasonable adjustments he requested for a job interview. Alternatives to interview, such as shadowing or job trial, could also be considered.

Examples of Reasonable Adjustments during the recruitment process

Before an interview, you could be:

- provided with as much notice as possible of when, where and how long the interview will be and how many interviewers / who they will be and given an overview of the interview format.

- offered a visit prior to the interview/assessment.

- asked if you have a preference for a phone or video/online interview rather than face-face.

- provided with an agenda, topics or questions in advance to all candidates. 24 hours is ideal, because a shorter interval (e.g., an hour before) still disadvantages a candidate who has difficulty processing information when anxious.

- provided with written confirmation of adjustments.

- offered a discussion with a member of the team prior to the interview to help them fully prepare, so provide a clear contact.

During the interview you could be:

- given questions in written format in a large print, one at a time, to support memory/focus.

- allowed extra time for interviews to reduce pressure and allow time to formulate thoughts.

- asked direct and specific questions.

- allowed to bring notes to refer to.

- offered and allow rest and/or movement breaks.

- asked to talk about a real case rather than a hypothetical one.

- allowed access to accessibility equipment, as well as extra time if asked to do a written task.

Additional Resources for interviews

Reasonable adjustments for interviews and assessments Employment Autism

Recommended interview adjustments for ADHD (adhduk.co.uk)

Disclosing a disability or neurodivergence

Disclosing a disability to your employer

There is no legal requirement for a person to declare a disability, including neurodivergence. Opportunities to disclose include application form, during an interview, during occupational health screening, or when already working. Early disclosure may allow a person to feel more control as to when and how their diagnosis is shared and what support can be put in place.

If a person is already employed, a union representative, advocate, or an identified ally can be present when they disclose. Disclosing neurodivergence does not automatically generate a referral to occupational health, although employers should offer this.

An employer does not have any obligations to make reasonable adjustments if they are unaware of any conditions that may require additional support. However, “Employers have a duty to provide reasonable adjustments where they know, or reasonably ought to have known, the worker, job seeker or former employee was disabled,” (UNISON, 2019).

The disclosure of a neurodivergent condition can be complex. If a person is confident to disclose prior to starting a job, it may reduce difficulties surrounding performance management as adjustments can be put in place at an early stage.

“Started my new job today and for the first time ever… I said I was proud to be a brain injured, neurodivergent person… now I’m able to see all the positives it has given me, I would not imagine that a year ago! ❤️❤️❤️”

Up to three quarters of neurodivegent people do not disclose their diagnosis due to fear of discrimination (Lindsay et al, 2021; Wissell et al, 2022) and half regret their decision to disclose (Westminster AchieveAbility Commission, 2018). Non-disclosure also leads to poor mental health outcomes associated with ‘masking’ (Kidwell et al, 2023).

This fear is not unfounded, as many individuals have reported negative comments or being treated differently after disclosure, such as, comments about working memory (Simpson, 2023), being told that “you don’t look ADHD/Autistic”, or having spelling and grammar mistakes made fun of. If someone discloses this information to you, instead, you should thank them for their openness and ask if there is anything you can do to support them.

Disclosure of a condition allows for legal protection against discrimination, and this covers application forms, interviews, offers of employment, pay, promotion, training opportunities, dismissal, redundancy, discipline and grievance (Equality Act, 2010).To be classed as having an impairment, a person does not need a diagnosed medical condition so long as its impacts are considered substantial and long-term (Citizens Advice, 2023).

| Kate’s Story – Disclosure of Autism prior to the interview process

I disclosed my Autism diagnosis when I applied for the job and requested time to look through the questions prior to the interview. This gave me time to process the questions and helped me settle and feel less anxious. I disclosed my diagnosis at my Occupational Health Screening. This triggered the HR department to carry out a risk assessment and identify potential support. HR and my manager were very supportive in making reasonable adjustments and have been constantly willing to listen to my concerns and experiences and put into place the necessary support as this changed. My experience of disclosure has been nothing but positive, which has made me feel comfortable in sharing my diagnosis. Because I feel comfortable and accepted, I find myself masking much less than in previous roles and that I am accepted as my true Autistic self. |

Alternative ways of disclosing a disability or neurodivergence

Some people find it helpful to disclose their accessibility requirements in their email signature. This might include use of hashtags, such as #ActuallyAutistic or an accessibility statement. Employers should consider modelling the use of accessibility statements to encourage normalisation, thus removing shame and stigma associated with disability.

Examples of accessibility needs in emails

Example 1

This communication has been written by a dyslexic person. If you have any trouble with the meaning of any of the sentences or words, please do not be afraid to ask for clarification.

Please expect creative thinking & creative spelling.

Example 2

Accessibility:

Accessibility: I am autistic/ADHD (AuDHD)

- Please expect creative thinking and honest/direct communication.

- Bullet points and deadlines are great if you need me to action something.

- Please send me a text, email or i-message to request a call back and leave a reason so I can prioritise your call.

Example 3

Accessibility requirements:

Please send all emails in Arial font size 12 or bigger.

If there are any action points for me to complete please bold and underline these.

Example 4

I aim to be an inclusive communicator. Please let me know if you have any preferences/needs in terms of how you would like to keep in contact.

Do I need to disclose my neurodivergence or diagnosis to HCPC?

Standard 6.3 of your HCPC Standards of conduct, performance, and ethics says:

“You must make changes to how you practise, or stop practising, if your physical or mental health may affect your performance or judgement, or put others at risk for any other reason.”

HCPC advises that qualified SLTs only need to inform them of a health condition or disability if you are unable to practise safely and effectively, even after reasonable adjustments have been put in place.

“You do not need to tell us if your health condition does not affect your practice or you are sure you can adapt, limit, or stop your practice as needed to remain safe and effective. In other words, you do not need to tell us so long as you can meet standard 6.3” (HCPC, 2023).

HCPC (2023) have provided a flowchart to support decision-making around whether a disability or health condition needs to be declared.

Information about Health, Disability and becoming a health and care professional can be found on the HCPC website.

Further resources

- Supporting Autistic people who may want to disclose (Autism Spectrum Australia, 2022)

- UNISON Reasonable Adjustments Bargaining Guide Model Policy & Accessibility Passport 2019

- GMB Union: Neurodiversity in the Workplace Toolkit (2018)

- Practice-Based Learning (PBL) for Neurodivergent Students

Asking for reasonable adjustments

Many neurodivergent people report challenges identifying their own needs and often do not know where to start when considering workplace adjustments. The following advice is not a conclusive list nor intended to be a one-size-fits-all and should not be a replacement for formal assessment of needs by Occupational Health, Access to Work or equivalent.

“My ADHD strategy coach has been an invaluable support for 2 years. Initially, they acted as a workplace counsellor and confidant – supporting me through discrimination and periods of self-doubt. They helped me find ways to streamline my workload and when these didn’t work, to apply for Access to Work for a job aide. I wouldn’t be where I am today without the support of my coach.”

The onus has often been placed on individuals to express their own needs, however it is important for employers to engage in their own research to understand the unique differences of neurodivergent employees. Many employers may provide well-being services, disability networks or union representatives that may be able to advise and support further.

“Working with a support worker/job aide: We encountered some barriers with my work preventing my aide from having access to IT programmes, emails and the printer. This means my support worker needs to be with me at all times instead of doing their job aide role. …Because this support is so novel, it is becoming a harder fight than we realised. Ultimately, it is becoming more difficult to do my job for worrying and organising my own support worker. I hope in future this will become easier for others like me.”

It is important to also consider the impact of some personal strategies, which may require large amounts of mental or emotional effort to maintain, be unsustainable for some individuals, or contribute to long-term changes in mental health and wellbeing. Many neurodivergent people have relied on masking their difficulties for many years at great personal cost, including physical exhaustion, burnout, inflammatory health conditions and anxiety (Pearson & Rose, 2023).

My experience of getting reasonable adjustments in place

Getting the adjustments and support I need to succeed has been like dragging a boulder up a mountain in a hurricane. It’s been 3 years of fighting, discomfort and difficult situations with employers. Access to Work support has been invaluable. I have had various different supports. The most beneficial were:

- Support worker/Job Aide

- Flexible work times

- ReMarkable 2

- Work phone

- ADHD strategy coaching

- Noise cancelling headset

- Standing desk

- eScribe Kindle

Examples of neuro-affirmative adaptations and reasonable adjustments

Not every adaptation or adjustment will be possible within every workplace, nor will every suggestion work for every individual or team. We recommend working through Developing a neuro-affirmative approach to supporting neurodivergent colleagues in our guidance to Support for those working with or managing neurodivergent colleagues to highlight your strengths and needs, and completing a profile in your Health Adjustments Passport. This will support discussions around most appropriate adjustments by increasing self-awareness and self-advocacy.

The suggestions below are not an exhaustive list and should not replace a full holistic assessment of needs, which may be individual and context dependent. These suggestions may be implemented by the individual or by those managing, supporting, or working alongside them. Others may require input at a service or facilities level as well as by those managing and supporting ND colleagues (see our guidance for managers and colleagues)

Many of the below suggestions may be beneficial for the whole team and not just the neurodivergent individual.

Documenting Neurodivergent strengths and needs

Health Adjustment Passport template, NHS Employers

Adjustments for Executive functioning

Consider employing a neurodiversity coach (available through Access to Work) for support making substantial and long-term changes or a job aide (personal assistant) where additional support may still be required after adjustments.

Perspectives/thinking

- Set clear agendas in advance to give time for preparation. Include the purpose of meeting/topics and what is expected so there is time to think about this in advance.

- Allow time to process changes in processes or environments with clear timescales and references to the implications of these changes. Consider whether additional mentoring or learning time is needed during periods of change.

- Use alarms to warn of transitions between activities. Physical signals to end/start an activity, e.g. move to a different room/seat, comfort breaks, listen to a song, make a drink.

- Create predictable routines e.g. block out diary for set tasks each day; avoid multitasking.

- Reduce distractions: Mute emails or use low-distraction devices e.g. Remarkable2.

- Provide additional time to talk through thoughts and ideas, e.g. informal check-ins.

- Hot-desking can be difficult due to different set-ups between desks and may lead to increased stress levels.

Organisation, planning, prioritising

- Use Workplace Mentors or neurodiversity coaches who help problem-solve any challenges. This might include exploring ways of working or learning styles that are strengths for the person. It can be helpful to explore this as a team building exercise, where acceptance is the aim.

- Prioritisation tools such as Eisenhower Matrix, flow charts or templates.

- Provide timescales/deadlines for tasks, with additional processing time, if needed.

- Provide dedicated places to store equipment with shelf labelling.

- Break tasks into smaller manageable chunks/detailed steps.

- Use digital task lists; set to ping when completed; small wins can provide satisfaction.

- Hold regular check-ins for project work or peer caseload supervision, with a clear process of support for any issues between sessions.

Memory

- Use a notepad / mini whiteboard / sticky notes to hold thoughts when interruptions are inappropriate. These may also help when organising multiple ideas /thoughts, e.g. for clinical reports.

- Use strategies to adapt training and learning to suit the individual e.g. 1-to-1 training allowing the employee to learn new systems at their own pace.

- Have agreed tasks followed up using your preferred communication style (e.g. in writing).

- Use of subtitles, transcripts, recordings, make notes to aid memory.

- Use of reading and writing aids.

- Movement may aid focus/creativity during meetings/training e.g. fidget tools, not sitting still for prolonged periods.

Time management

- Use of timers, alarms or digital reminders to keep focussed. A timed music playlist may provide an auditory time limit – consider what works best for you.

- Working in the office may provide more structure or visual cues for some individuals (e.g. reminder to eat lunch when you see others stopping), however, this may be a source of distraction for others.

- Weigh up the benefits of home versus office or hybrid working for reducing distractions during non-client facing aspects of job role.

- Careful management of diary e.g. allowing extra time for more challenging tasks.

- Regular check-ins for projects.

- Pre-agreed flexible working or buddy system to enable completion of work within your contracted hours. See also body doubling which may be of benefit.

- Schedule screen breaks for longer tasks; add movement, music or comfort breaks.

- Pomodoro Technique may aid focus on a task,

- Consider whether job plans are realistic. A workplace stress assessment may identify areas of stress across teams.

Attentional Control

- Have an informal work buddy to keep you focussed. This might be agreed informally with a colleague or as a job aide funded by Access to Work.

- Consider the impact of the sensory environment and flexibility around workspaces to meet sensory needs, which may fluctuate day-by-day.

- Reduce office distractions (noise/odours/busyness); use quiet spaces, working from home, active noise cancelling headphones/earbuds, low level music/brown noise/white noise (whilst being mindful of colleagues sharing the space), use ‘do not disturb’ settings on emails/ virtual working platforms (e.g., MS Teams), consider using door signs or visuals to inform colleagues when you need to focus or not be disturbed.

- Agree how you will be included in group conversations or meetings. Consider whether working memory, processing time or sensory needs are impacting and actively problem-solve.

- Use of fidget toys/focus tools to manage movement needs

- Use of document readers /speech to text functions to aid focus.

- Low-distraction devices such as Remarkable2 or similar may help maintain focus.

Additional Resources

Workplace Adjustments for Executive Dysfunction Neurodivergent Emabler

Executive Dysfunction after brain injury factsheet

My First ADHD Coaching Session: My Honest Review – YouTube

Examples of whole workplace adaptations

Many workplace adaptations benefit all staff and could be normalised by considering whole workplace environmental or procedural adaptations. Workplaces should be open to reflect on whether systems and practices could be adapted to accommodate these differences, often to the benefit of all colleagues, rather than placing the sole responsibility on the ND person to adapt and change. For further specific examples of adjustment suggestions (ie office design), see our guidance, for managers and colleagues.

Training needs

- Facilitate training designed and/or delivered by neurodivergent staff to ensure ongoing curiosity, reflection, and awareness of neurodivergence throughout the team.

- Actively work to remove stigma, unconscious bias, stereotyping and assumptions about mental health / neurodivergence – ensure training does not reinforce these.

- Continually strive to identify and remove barriers to communication between staff.

- Consider further support or training in supporting neurodivergent staff, e.g. trauma- informed resilience frameworks, Mental Health First Aid, supervision training that includes understanding and respecting neurodivergent communication differences.

Additional Resources

Creating Inclusive Workplaces for All Catarina Rivera | TEDxRolandPark

Adjustments for Sensory differences

We recommend completing a sensory screen irrespective of neurodivergence due to the high incidence of co-occurring divergences. Access to Work may provide further support and advice. More information on sensory differences including online checklists and sensory toolkits can be found in this section.

For adjustments which can be made by your colleagues, managers and workplace (eg: controlling Smells, temperature and lighting) see our guidance on Support for those working with and/or managing neurodivergent SLTs.

Noise

- Use Noise cancelling headphones/earbuds for video meetings, office space, wards, schools etc. There are different types of in-ear devices that provide different levels of noise filtering.

- Consider hybrid/agile working to allow time/space for sensory/social regulation e.g. if quiet space in busy settings, such as wards, is not available, could a person work from home or another base for non-client-facing aspects of the role e.g. clinical notes?

- Consider the sensory impact of noises within the workplace, replace noisy keyboards with soft touch, position of desks in relation to air conditioning, avoid eating noisy foods at desk when others are working (see also Misophonia).

Movement

- Take Movement breaks after sitting for long periods – fidgeting or moving around may be considered necessary. Consider fidget tools or access to outdoor or breakout spaces.

- Use Adapted office equipment, e.g. height adjustable desks, seating balls, filters for screens. Many workplaces complete display screen equipment assessments for all staff as part of health and safety policies.

- Consider how colleagues approach each other; approach from the front, and be mindful of touch and sudden sounds, visuals or movement. Consider contacting colleagues using emails or i-messenger to arrange a time to meet.

Smells/temperature/lighting/textures

- Use desk lamps in areas of low-level lighting.

- Clutter-free workspace policies (required by many infection control policies).

- Consideration of the sensory impact of smells within the workplace e.g. people eating at their desks, open kitchens near work spaces when creating policies or office designs.

- Consider adjustments to uniform that still meet infection control requirements.

Adjustments for Communication and Language Differences, including differences in auditory and/or language processing

While SLTs are expected to have a high-proficiency of English Language, to be a profession which is representative of the communities that we serve, different communication styles should be accepted. Communication abilities are known to fluctuate across different times, settings, social situations, and levels of fatigue, arousal, or distress. Neurodivergent individuals may be highly effective communicators, particularly with other neurodivergent individuals (Milton, 2017).

SLTs should aim to enable and encourage effective communication using the means which are most accessible to the individual at the time, which may include written language and/or AAC. The use of alternative (non-speaking) means of communication may also foster empathy with AAC users, encourage lived-experience expertise, and promote modelling of AAC. Where there are legitimate concerns around English language proficiency, this should be raised sensitively with access to the appropriate support systems and standards of proficiency.

Communication

- Identify communication styles, which may include the ability to understand non-literal or non-verbal language (body language, facial expressions), direct use of language, or a preference for text-based communication. If an individual is comfortable with this, they may consider sharing their communication style with service users, parents, carers etc ahead of appointments.

- Encouraging whole teams to create their own one page communication profiles to share with colleagues removes stigma and encourages empathy towards both colleagues and service users. Before implementing, consider whether individuals would feel comfortable with this information being shared with the wider team and if it is an appropriate exercise.

- Take time to learn about experiences of individuals who are ‘semi-speaking’. Accept that within some situations, some individuals may prefer or need to use written communication and/or AAC. This should be treated with respect and curiosity and not necessarily judged as a measure of competence. Utilising non-speaking communication means may also promote empathy, modelling, and lived-experience expertise.

- Minimise expectations to engage in small talk (including in emails) or social events (recognise some may want to engage in small talk but are not sure how to do this).

Language

- Consider using alternative non-speaking ways of communicating (e.g. writing down tasks), which may support memory/processing.

- During large group activities, where possible, group discussions are better in a quiet breakout room rather than with multiple groups in the same room.

- Ask for background noise to be turned off /close doors e.g. during appointments.

- Provision of summaries and key points, alongside or instead of, detailed reports where possible with recognition that this will not always be possible. Consider the use of AI to provide summaries of published online reports.

- Check understanding of instructions, providing further detail or repetitions where required.

- Consider alternative technologies to note take and record meetings e.g. Smart Pen

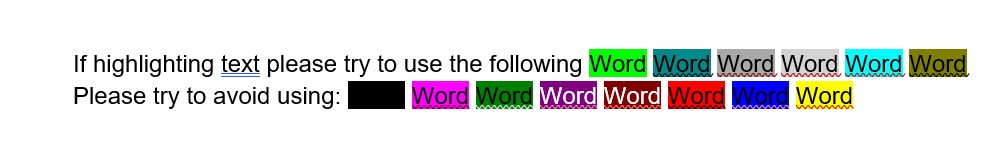

Adjustments for Acquiring and demonstrating knowledge: Literacy/numeracy

Understand that challenges are not a reflection of knowledge, skills or intelligence.

Learn more about acquiring and demonstrating knowledge. People with neurodivergence that affects learning are likely to have needs in Executive functioning.

Consider referral to Access to Work for full assessment and funding for software or equipment. Access to Work is able to make up-to-date recommendations based on need. These recommendations may include (but are not limited to):

- having someone to proof-read/help with calculations; consider peer supervision/admin support

- recommendations around the ideal size/spacing/amount of text used within correspondence and presentations

- using pen grips or an ergonomic mouse

- using dyslexia fonts, screen ruler, screen shading or other accessibility settings for computers

- any reading for meetings to be sent in advance, in an editable format with a clear agenda to allow additional time to read /retain /reflect on information.

- the provision of summaries and key points, rather than full reports where possible

- using text to speech software to read back and check your written work.

- primarily focus on accuracy, before considering speed on tasks

- being provided adequate time for learning new tasks

Resources

Be aware that regular software is being updated with new accessibility features all the time and will vary between electronic data recording systems. This is not an exhaustive list, but provides some options at time of writing.

Book time with your IT department or service to learn about local accessibility features. Employers could consider making training videos available to all as many people benefit from these tools.

Examples of free accessibility software for Windows / Internet browsers:

- MS Word document reader tutorial

- PDF document reader tutorial

- Word dictate function tutorial

- Pixie: Accessibility Reader for Google Chrome

- Accessibility features of Microsoft Edge

- Grammarly (free grammar checking software)

Assistive Technology examples

- Intro to Dyslexia Assistive Tools video

- Dragon accessibility software

- Claro accessibility software

- Smart pens e.g. Livescribe

- The Best Note-taking Tablets for ADHD and Neurodiversity

- Transcribing app examples: Just Press Record , Otter

Dyslexic fonts (Google Chrome)

Once installed, they convert everything on your screen, including websites:

General Information

Adjustments for Mental Health, Wellbeing & Emotional Regulation

Ensure an honest reflection on judgements or assumptions resulting from unconscious bias, stigma and outdated stereotypes about neurodiversity and mental health, including atypical expressions of emotion. Learn more about burnout and masking, which are main contributors to mental health needs in neurodivergent employees.

Wellbeing support

- Putting a Wellness Plan in place.

- Using Access to Work funding for mental health support.

- Implementing a Buddy system or a Trusted Ally that the person identifies with who can check in with as needed; consider Mental Health First Aider training for that person.

- Additional supervision / mentoring / coaching, peer caseload supervision, health and well-being supervision; provided by one or more people, or outsourced e.g. ND coach.

- Supportive, non-judgemental relationships are essential for ‘brave’ conversations.

- Psychological therapies, counselling; individuals may prefer to have a practitioner with professional or lived experience of neurodiversity.

- Consider local wellbeing provisions, e.g. access to disability networks or neurodiversity peer support groups (in work time), Employee Assistance Programmes, etc. Individuals may need to self-refer to these, or referrals may be supported by managers or occupational health services.

Reducing anxiety

- Psychological safety is essential in supporting well-being; noticing and not judging.

- Consider triggers for anxiety (e.g. interpersonal, sensory, changes, certain tasks) and whether these can be minimised or avoided.

- Ensure there are clear expectations and processes for all aspects of the job role.

- Have a plan in place that considers if support is needed during times of change.

- Where possible, be provided with and allowed to go to a quiet place which if you need time alone.

Reducing fatigue/burnout prevention

- Honest consideration of contributors to burnout (e.g. sensory, social, interpersonal, environmental factors); consider ND workplace assessment via Access to Work.

- For meetings, consider if attendance is necessary, with the possibility of reading minutes afterwards or utilising alternative ways to contribute to group decisions.

- Some people may need support to consider practical options for reducing fatigue that work for both the individual and the service e.g. scheduled breaks, agreed timeout options (e.g. mute/turn off video, moving away from task or screen, going for a walk, making a drink – any activity that aids emotional, sensory or physical ‘reset’)

- Support may be needed to put a plan in place to manage work-life balance if you regularly overwork when in hyperfocus, e.g. through flexible working, time in lieu or check-ins / end of day buddy.

- Supervision with or delegation of an overwhelming task and/or caseload, such as support with non-clinical admin tasks.

- Balance social and sensory demands throughout the day/week to reduce chronic overwhelm without rest and recovery time e.g. break up face to face appointments with admin time between, working from home several days a week.

- Is a disability policy available that has flexibility around absence trigger points?

Crisis support

- Samaritans Calls are free 116 123 – jo@samaritans.org

- SHOUT UK’s 24/7 Crisis Text Service for Mental Health Support – TEXT 85258

- Brain in Hand app/service with access to 24/7 emotional regulation support

- MIND have local support hubs as well as local support lines

Additional resources

- Workplace Needs Assessments for specific Neurodiversities Exceptional Individuals

- Workplace health needs assessment (Public Health England). Practical advice for employers on workplace health and a tool for carrying out workplace health needs assessments.

- Guidance and tools for digital accessibility

- 10 Reasonable Adjustments for Employee Mental Health

Access to work

Access to Work is publicly funded and aimed at supporting those with a disability, illness or health condition who need support to find or remain in work. Individuals must self-refer via telephone or online. Support is individualised but can include:

- A grant to fund practical support (such as specialist equipment/software, help from support workers such as a BSL interpreter, job coach or travel buddy, physical workplace / vehicle adaptations, or cost of travel if unable to access public transport.)

- Mental health support – including an individualised plan to find or stay in work, or 1:1 sessions with a mental health practitioner.

- Funding to provide communication support for job interviews.

Access to work will not pay for reasonable adjustments to help you do your job. Your employer is legally required to make these reasonable adjustments and/or changes. Access to Work can tell your employer if reasonable adjustments are needed.

“My workplace bought the eScribe Kindle for me despite AtW recommending the reMarkable2 tablet. The eScribe has a busy dashboard that is not accessible for an ADHDer and highly distracting. This has happened on multiple occasions where workplaces will cut corners and buy cheaper equipment.”

To be eligible to apply for Access to Work you must:

- Have an illness, health condition or disability which impacts on your ability to do your job or travel to and from your workplace. This includes all forms of neurodivergence as well as physical or sensory disability / differences, or mental health needs.

- Be at least 16 years old.

- Be in paid work (or be about to start paid work in the next 12 weeks) This can include full or part time work, self-employment, an apprenticeship or a work placement.

- Live and work (or be about to start work) in England, Scotland or Wales.

- You do not need to have a diagnosis to be eligible for Access to Work; support is not dependent upon your salary or savings, and you can claim alongside other benefits.

See the Access to Work website for further information about eligibility and how to apply. Your application will be fast-tracked if you are starting a new job.

Experiences of applying for Access to Work

Applications are done online / phone. It takes 5-8 months to get an assessment. You can tell them what you need, if you’re not sure, they will do a holistic assessment. People have found this to be thorough and supportive of unique neurodivergent needs.

If you are starting a new job, you get prioritised. Jodee was allocated an assessor within 2 days and they called the following week. Jodee knew what she wanted and was awarded the funding by the end of the week, which meant that she was able to get the things she needed to start her new job.

The holistic assessment is by video call or in person. They do a report, but you have to supply 3 quotes for each thing you need. They will award funding for the cheapest, so make sure the thing you want is the cheapest quote.

Charlotte says, “It has helped a lot, especially training and mentoring. The process is easy and very helpful. I have found it useful to have some idea of what you might want and to look at possible sources before your assessment and to do research on the companies being suggested for mentoring / training and see how others have found them.”

Applications for Mental Health support are processed quickly with assessments completed within 3 weeks and support soon after.

Mental Health support review: “I wish I’d read the reviews before I chose which service to use. I get a phone call every few weeks and they send me self-help guides…. nothing was adapted for neurodivergence. I had a mental health crash, but my mental health coach called me straight away and booked an emergency review with my GP. I wasn’t in a position to call them myself or tell my family, so I was glad they were there to help when I was in crisis.”

Contributors

Lead authors and editors

Jodee Simpson

Polly Davis

Co-authors

Wing Yee Lam

Kate Harvey

Laura Chapman

Claire Ryan

Charlotte Stace

Jessica Hunter

Harriet Richardson

Lily Scanlan

Samantha Cobbing

Shannon Dutton-Noll

Sarah Philpott

Angela May

Anna L Knight

Other Contributors

Kristina Ásdís

Anonymous members of NDSLTUK who provided feedback, reviewed content, advised us on wording and terminology or shared their stories

Download as PDF

Download as PDF